Spine & Joint

Lumbar Disc Prolapse

A herniated disk is a condition that can occur anywhere along the spine, but most often occurs in the lower back. It is sometimes called a bulging, protruding, or ruptured disk. It is one of the most common causes of lower back pain, as well as leg pain or “sciatica.”

Between 60% and 80% of people will experience low back pain at some point their lives. Some of these people will have low back pain and leg pain caused by a herniated disk.Although a herniated disk can be very painful, most people feel much better with just a few weeks or months of nonsurgical treatment.

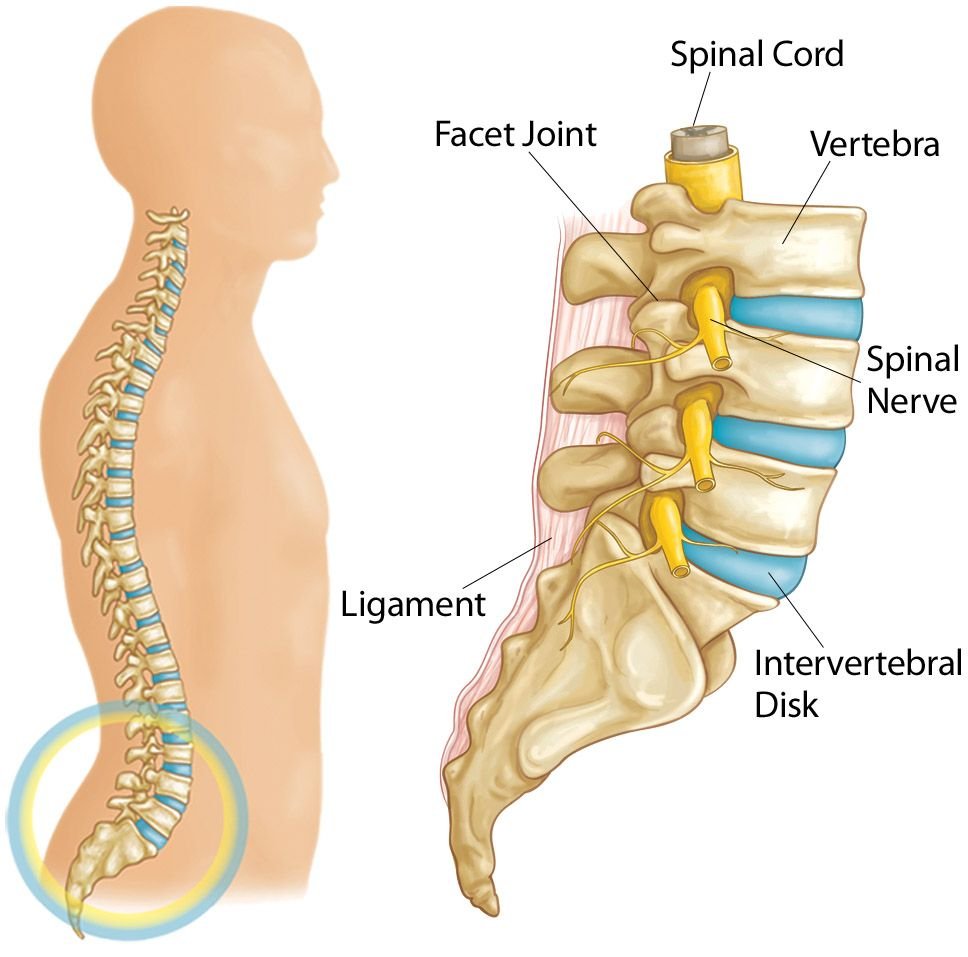

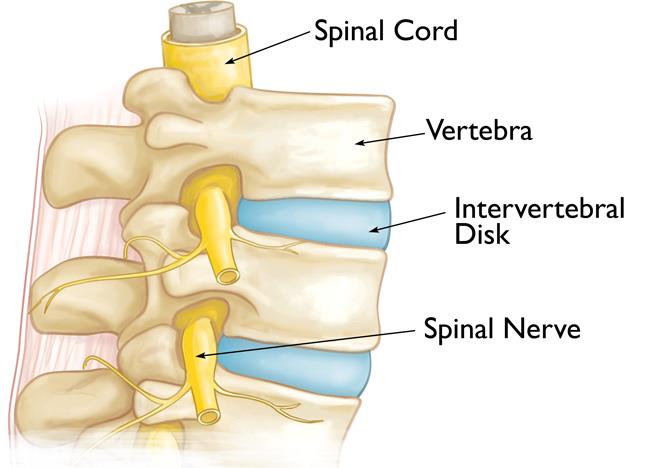

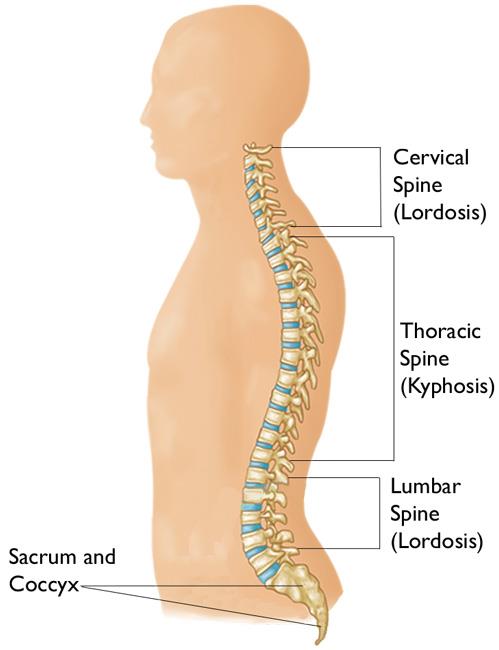

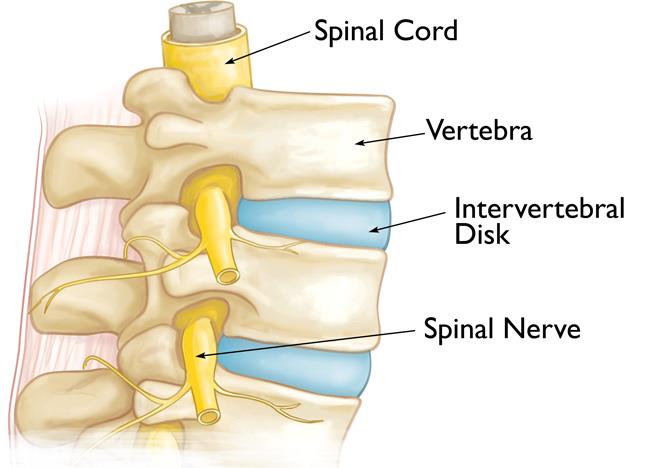

Your spine is made up of 24 bones, called vertebrae, that are stacked on top of one another. These bones connect to create a canal that protects the spinal cord.

Five vertebrae make up the lower back. This area is called your lumbar spine.

Other parts of your spine include:

Spinal cord and nerves. These “electrical cables” travel through the spinal canal carrying messages between your brain and muscles. Nerve roots branch out from the spinal cord through openings in the vertebrae.

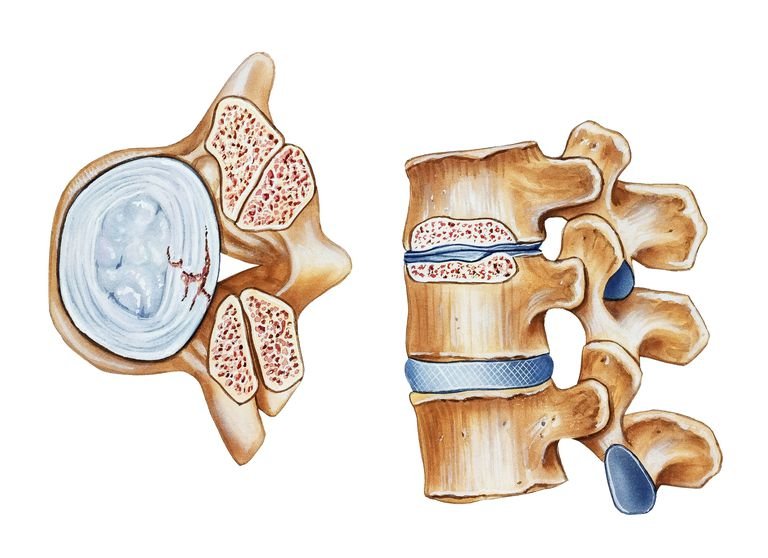

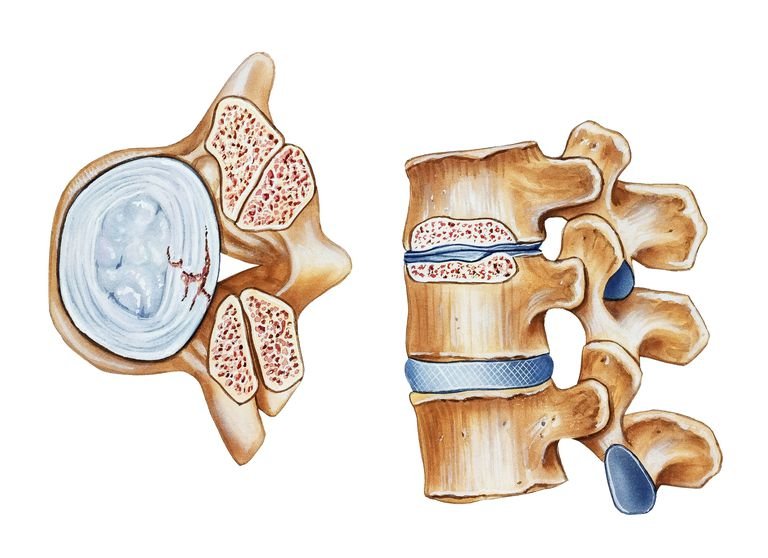

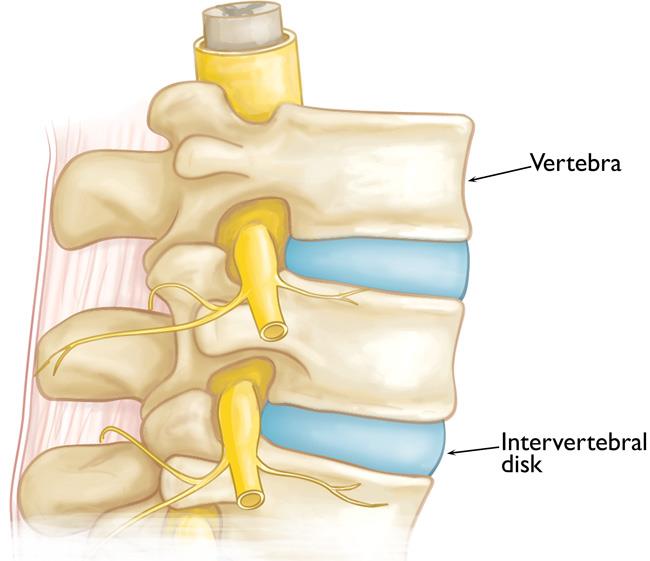

Intervertebral disks. In between your vertebrae are flexible intervertebral disks. These disks are flat and round, and about a half inch thick.

Intervertebral disks act as shock absorbers when you walk or run. They are made up of two components:

- Annulus fibrosus. This is the tough, flexible outer ring of the disk.

- Nucleus pulposus. This is the soft, jelly-like center of the disk.

A disk begins to herniate when its jelly-like nucleus pushes against its outer ring due to wear and tear or a sudden injury. This pressure against the outer ring may cause lower back pain.

If the pressure continues, the jelly-like nucleus may push all the way through disk’s outer ring or cause the ring to bulge. This puts pressure on the spinal cord and nearby nerve roots. In addition, the disk material releases chemical irritants that contribute to nerve inflammation. When a nerve root is irritated, there may be pain, numbness, and weakness in one or both of your legs, a condition called “sciatica.”

A herniated disk is most often the result of natural, age-related wear and tear on the spine. This process is called disk degeneration. In children and young adults, disks have high water content. As people age, the water content in the disks decreases and the disks become less flexible. The disks begin to shrink and the spaces between the vertebrae get narrower. This normal aging process makes the disks more prone to herniation.

A traumatic event, such as a fall, can also cause a herniated disk.

Certain factors may increase your risk of a herniated disk. These include:

Gender. Men between the ages of 20 and 50 are most likely to have a herniated disk.

Improper lifting. Using your back muscles instead of your legs to lift heavy objects can cause a herniated disk. Twisting while you lift can also make your back vulnerable. Lifting with your legs, not your back, may protect your spine.

Weight. Being overweight puts added stress on the disks in your lower back.

Repetitive activities that strain your spine. Many jobs are physically demanding. Some require constant lifting, pulling, bending, or twisting. Using safe lifting and movement techniques can help protect your back.

Frequent driving. Staying seated for long periods, plus the vibration from the car engine, can put pressure on your spine and disks.

Sedentary lifestyle. Regular exercise is important in preventing many medical conditions, including a herniated disk.

Smoking. It is believed that smoking lessens the oxygen supply to the disk and causes more rapid degeneration.

In most cases, low back pain is the first symptom of a herniated disk. This pain may last for a few days, then improve. Other symptoms may include:

- Sciatica. This is a sharp, often shooting pain that extends from the buttock down the back of one leg. It is caused by pressure on the spinal nerve.

- Numbness or a tingling sensation in the leg and/or foot

- Weakness in the leg and/or foot

- Loss of bladder or bowel control. This is extremely rare and may indicate a more serious problem called cauda equina syndrome. This condition is caused by the spinal nerve roots being compressed. It requires immediate medical attention.

Cervical Disc Prolapse

Your vertebrae are cushioned by round, flat discs. In a healthy state they act like shock absorbers. If they bulge or break or rupture, they cause Cervical Disc Prolapse (herniated disc or slipped disc). Herniated disc is more common in the neck and lumbar spine due to the wear and tear of the disc as we age. Practically everybody suffers from neck pain after 30 – 40 years age, which is a part of their life. But, of late, cervical disc prolapse is affecting even very young patients as well, due to utter negligence and lifestyle related issues like erratic and careless driving, improper positioning while working at the desks, etc. Let us understand cervical disc prolapse symptoms, consequences and treatment.

Pain, numbness or weakness in neck, chest, arms, shoulders, hands; weakness in the upper limbs; and, the whole body with difficulty in walking are the symptoms of Cervical Disc Prolapse. Sometimes you may experience unusual tingling in other parts of the body including your legs as well.

Cervical Disc prolapse has become a frequent condition now. It may lead to neck pain, which spreads to either one or both the hands, and then usually leads to paralysis.

Earlier, this condition was treated by replacing the damaged disc with the patient’s own bone graft taken from the hip bone and fitting the vacant disc space with the metal cages or spacers; and then, fixing theadjacent vertebra with plates and screws. This procedure, used to block the movements at the fixed level, would risk the damage at the adjacent levels to the extent of prolapsing disc again. Therefore, the best treatment option is Cervical Disc Replacement.

Replacement of the damaged cervical disc with an artificial disc restores movement at that level so that adjacent discs are not subjected to increased strain – a subsequent prolapse. This is by far the best currently available treatment. Another best aspect rather great advantage of this artificial disc replacement is that patient need not have to take rest for months altogether, and can walk on the same day of surgery. Furthermore, the patient can resume his day-to-day activities within a few days after surgery. The patient need not have to wear cervical collars after the surgery.

Degenerative Disc Disease

Almost everyone will experience low back pain at some point in their lives. This pain can vary from mild to severe. It can be short-lived or long-lasting. However it happens, low back pain can make many everyday activities difficult to do.

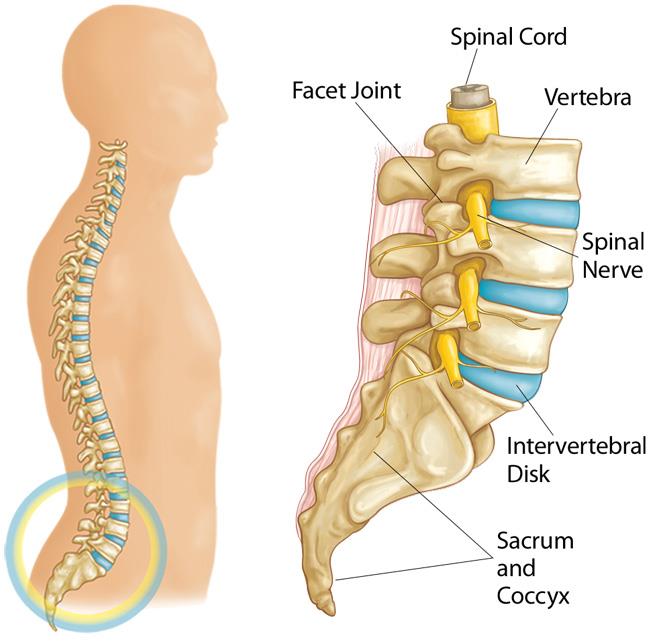

Your spine is made up of small bones, called vertebrae, which are stacked on top of one another. Muscles, ligaments, nerves, and intervertebral disks are additional parts of your spine.

Understanding your spine and how it works can help you better understand low back pain. Learn more about spine anatomy: Spine Basics

Back pain is different from one person to the next. The pain can have a slow onset or come on suddenly. The pain may be intermittent or constant. In most cases, back pain resolves on its own within a few weeks.

There are many causes of low back pain. It sometimes occurs after a specific movement such as lifting or bending. Just getting older also plays a role in many back conditions.

As we age, our spines age with us. Aging causes degenerative changes in the spine. These changes can start in our 30s — or even younger — and can make us prone to back pain, especially if we overdo our activities.

These aging changes, however, do not keep most people from leading productive, and generally, pain-free lives. We have all seen the 70-year-old marathon runner who, without a doubt, has degenerative changes in her back!

One of the more common causes of low back pain is muscle soreness from overactivity. Muscles and ligament fibers can be overstretched or injured.

This is often brought about by that first softball or golf game of the season, or too much yard work or snow shoveling in one day. We are all familiar with this “stiffness” and soreness in the low back — and other areas of the body — that usually goes away within a few days.

Some people develop low back pain that does not go away within days. This may mean there is an injury to a disk.

Disk tear. Small tears to the outer part of the disk (annulus) sometimes occur with aging. Some people with disk tears have no pain at all. Others can have pain that lasts for weeks, months, or even longer. A small number of people may develop constant pain that lasts for years and is quite disabling. Why some people have pain and others do not is not well understood.

Disk herniation. Another common type of disk injury is a “slipped” or herniated disc.

Herniated disk.

A disk herniates when its jelly-like center (nucleus) pushes against its outer ring (annulus). If the disk is very worn or injured, the nucleus may squeeze all the way through. When the herniated disk bulges out toward the spinal canal, it puts pressure on the sensitive spinal nerves, causing pain.

Because a herniated disk in the low back often puts pressure on the nerve root leading to the leg and foot, pain often occurs in the buttock and down the leg. This is sciatica.

A herniated disk often occurs with lifting, pulling, bending, or twisting movements.

Disk degeneration.

With age, intervertebral disks begin to wear away and shrink. In some cases, they may collapse completely and cause the facet joints in the vertebrae to rub against one another. Pain and stiffness result.

This “wear and tear” on the facet joints is referred to as osteoarthritis. It can lead to further back problems, including spinal stenosis.

Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis.

(Spon-dee-low-lis-THEE-sis). Changes from aging and general wear and tear make it hard for your joints and ligaments to keep your spine in the proper position. The vertebrae move more than they should, and one vertebra can slide forward on top of another. If too much slippage occurs, the bones may begin to press on the spinal nerves.

Spinal Stenosis

Spinal stenosis occurs when the space around the spinal cord narrows and puts pressure on the cord and spinal nerves.

When intervertebral disks collapse and osteoarthritis develops, your body may respond by growing new bone in your facet joints to help support the vertebrae. Over time, this bone overgrowth (called spurs) can lead to a narrowing of the spinal canal. Osteoarthritis can also cause the ligaments that connect vertebrae to thicken, which can narrow the spinal canal.

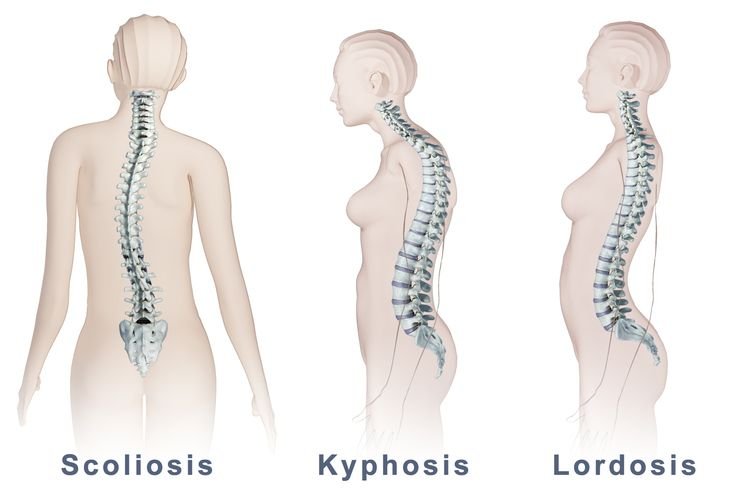

Scoliosis

This is an abnormal curve of the spine that may develop in children, most often during their teenage years. It also may develop in older patients who have arthritis. This spinal deformity may cause back pain and possibly leg symptoms, if pressure on the nerves is involved.

There are other causes of back pain, some of which can be serious. If you have vascular or arterial disease, a history of cancer, or pain that is always there despite your activity level or position, you should consult your primary care doctor.

Back pain varies. It may be sharp or stabbing. It can be dull, achy, or feel like a “charley horse” type cramp. The type of pain you have will depend on the underlying cause of your back pain.

Most people find that reclining or lying down will improve low back pain, no matter the underlying cause.

People with low back pain may experience some of the following:

- Back pain may be worse with bending and lifting.

- Sitting may worsen pain.

- Standing and walking may worsen pain

- Back pain comes and goes, and often follows an up and down course with good days and bad days.

- Pain may extend from the back into the buttock or outer hip area, but not down the leg.

- Sciatica is common with a herniated disk. This includes buttock and leg pain, and even numbness, tingling or weakness that goes down to the foot. It is possible to have sciatica without back pain.

Regardless of your age or symptoms, if your back pain does not get better within a few weeks, or is associated with fever, chills, or unexpected weight loss, you should call your doctor.

Spinal Canal Stenosis

Common cause of low back and leg pain is lumbar spinal stenosis.

As we age, our spines change. These normal wear-and-tear effects of aging can lead to narrowing of the spinal canal. This condition is called spinal stenosis.

Degenerative changes of the spine are seen in up to 95% of people by the age of 50. Spinal stenosis most often occurs in adults over 60 years old. Pressure on the nerve roots is equally common in men and women.

A small number of people are born with back problems that develop into lumbar spinal stenosis. This is known as congenital spinal stenosis. It occurs most often in men. People usually first notice symptoms between the ages of 30 and 50.

Your spine is made up of small bones, called vertebrae, which are stacked on top of one another. Muscles, ligaments, nerves, and intervertebral disks are additional parts of your spine.

Understanding your spine and how it works can help you better understand spinal stenosis. Learn more about spine anatomy

Spinal stenosis occurs when the space around the spinal cord narrows. This puts pressure on the spinal cord and the spinal nerve roots, and may cause pain, numbness, or weakness in the legs.

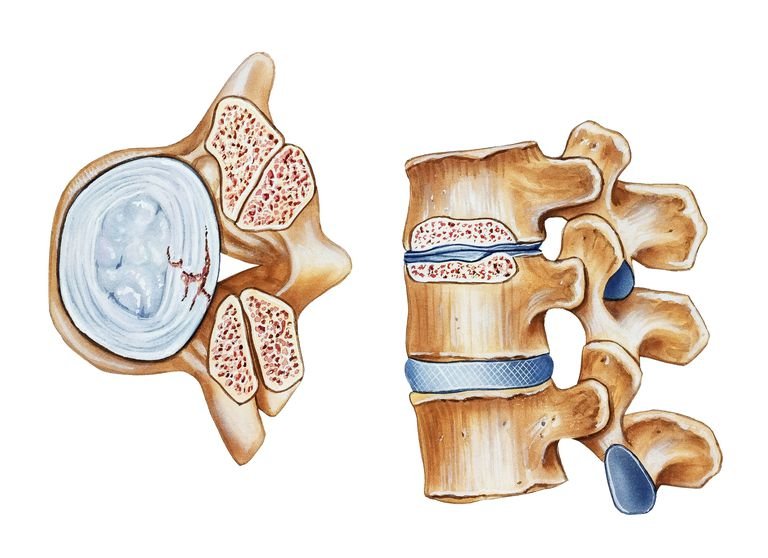

This illustration shows a healthy vertebra (cross-section view) and a vertebra with narrowing of the spinal canal, called stenosis.

Arthritis is the most common cause of spinal stenosis. Arthritis refers to degeneration of any joint in the body.

In the spine, arthritis can result as the disk degenerates and loses water content. In children and young adults, disks have high water content. As we get older, our disks begin to dry out and weaken. This problem causes settling, or collapse, of the disk spaces and loss of disk space height.

When we are young, disks have a high water content (left). As disks age and dry out, they may lose height or collapse (right). This puts pressure on the facet joints and may result in arthritis.

As the spine settles, two things occur. First, weight is transferred to the facet joints. Second, the tunnels that the nerves exit through become smaller.

As the facet joints experience increased pressure, they also begin to degenerate and develop arthritis, similar to that occurring in the hip or knee joint. The cartilage that covers and protects the joints wears away. If the cartilage wears away completely, it can result in bone rubbing on bone.

Arthritic bone spurs narrow the spinal canal.

To make up for the lost cartilage, your body may respond by growing new bone in your facet joints to help support the vertebrae. Over time, this bone overgrowth-called spurs-may narrow the space for the nerves to pass through.

Another response to arthritis in the lower back is that ligaments around the joints increase in size. This also lessens space for the nerves. Once the space has become small enough to irritate spinal nerves, painful symptoms result.

Back pain. People with spinal stenosis may or may not have back pain, depending on the degree of arthritis that has developed.

Burning pain in buttocks or legs (sciatica). Pressure on spinal nerves can result in pain in the areas that the nerves supply. The pain may be described as an ache or a burning feeling. It typically starts in the area of the buttocks and radiates down the leg. As it progresses, it can result in pain in the foot.

Numbness or tingling in buttocks or legs. As pressure on the nerve increases, numbness and tingling often accompany the burning pain. Although not all patients will have both burning pain and numbness and tingling.

Weakness in the legs or “foot drop.” Once the pressure reaches a critical level, weakness can occur in one or both legs. Some patients will have a foot-drop, or the feeling that their foot slaps on the ground while walking.

Less pain with leaning forward or sitting. Studies of the lumbar spine show that leaning forward can actually increase the space available for the nerves. Many patients may note relief when leaning forward and especially with sitting. Pain is usually made worse by standing up straight and walking. Some patients note that they can ride a stationary bike or walk leaning on a shopping cart. Walking more than 1 or 2 blocks, however, may bring on severe sciatica or weakness.

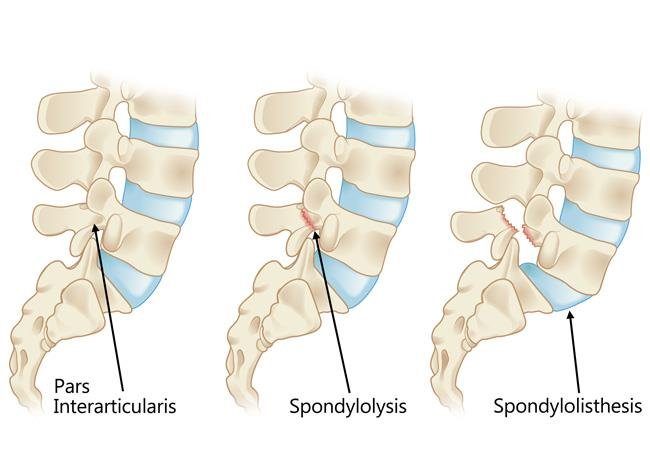

Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolysis (spon-dee-low-lye-sis) and spondylolisthesis (spon-dee-low-lis-thee-sis) are common causes of low back pain in young athletes.

Spondylolysis is a crack or stress fracture in one of the vertebrae, the small bones that make up the spinal column. The injury most often occurs in children and adolescents who participate in sports that involve repeated stress on the lower back, such as gymnastics, football, and weight lifting.

In some cases, the stress fracture weakens the bone so much that it is unable to maintain its proper position in the spine—and the vertebra starts to shift or slip out of place. This condition is called spondylolisthesis.

For most patients with spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis, back pain and other symptoms will improve with conservative treatment. This always begins with a period of rest from sports and other strenuous activities.

Patients who have persistent back pain or severe slippage of a vertebra, however, may need surgery to relieve their symptoms and allow a return to sports and activities.

Your spine is made up of 24 small rectangular-shaped bones, called vertebrae, which are stacked on top of one another. These bones connect to create a canal that protects the spinal cord.

Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis occur in the lumbar spine.

The five vertebrae in the lower back comprise the lumbar spine.

Other parts of your spine include:

Spinal cord and nerves. These “electrical cables” travel through the spinal canal carrying messages between your brain and muscles. Nerve roots branch out from the spinal cord through openings in the vertebrae.

Facet joints. Between the back of the vertebrae are small joints that provide stability and help to control the movement of the spine. The facet joints work like hinges and run in pairs down the length of the spine on each side.

Intervertebral disks. In between the vertebrae are flexible intervertebral disks. These disks are flat and round and about a half inch thick. Intervertebral disks cushion the vertebrae and act as shock absorbers when you walk or run.

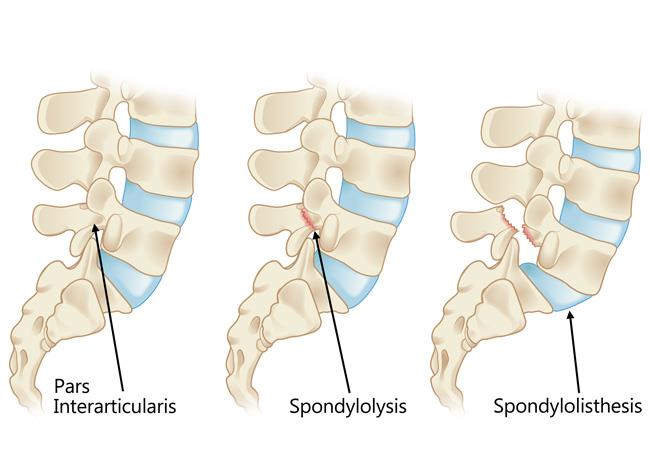

Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are different spinal conditions—but they are often related to each other.

Spondylolysis

In spondylolysis, a crack or stress fracture develops through the pars interarticularis, which is a small, thin portion of the vertebra that connects the upper and lower facet joints.

Most commonly, this fracture occurs in the fifth vertebra of the lumbar (lower) spine, although it sometimes occurs in the fourth lumbar vertebra. Fracture can occur on one side or both sides of the bone.

The pars interarticularis is the weakest portion of the vertebra. For this reason, it is the area most vulnerable to injury from the repetitive stress and overuse that characterize many sports.

Spondylolysis can occur in people of all ages but, because their spines are still developing, children and adolescents are most susceptible.

Many times, patients with spondylolysis will also have some degree of spondylolisthesis.

If left untreated, spondylolysis can weaken the vertebra so much that it is unable to maintain its proper position in the spine. This condition is called spondylolisthesis.

In spondylolisthesis, the fractured pars interarticularis separates, allowing the injured vertebra to shift or slip forward on the vertebra directly below it. In children and adolescents, this slippage most often occurs during periods of rapid growth—such as an adolescent growth spurt.

Doctors commonly describe spondylolisthesis as either low grade or high grade, depending upon the amount of slippage. A high-grade slip occurs when more than 50 percent of the width of the fractured vertebra slips forward on the vertebra below it. Patients with high-grade slips are more likely to experience significant pain and nerve injury and to need surgery to relieve their symptoms.

(Left) The pars interarticularis is a narrow bridge of bone found in the back portion of the vertebra. (Center) Spondylolysis occurs when there is a fracture of the pars interarticularis. (Right) Spondylolisthesis occurs when the vertebra shifts forward due to instability from the pars fracture.

Overuse

Both spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are more likely to occur in young people who participate in sports that require frequent overstretching (hyperextension) of the lumbar spine—such as gymnastics, football, and weight lifting. Over time, this type of overuse can weaken the pars interarticularis, leading to fracture and/or slippage of a vertebra.

Genetics

Doctors believe that some people may be born with vertebral bone that is thinner than normal—and this may make them more vulnerable to fractures.

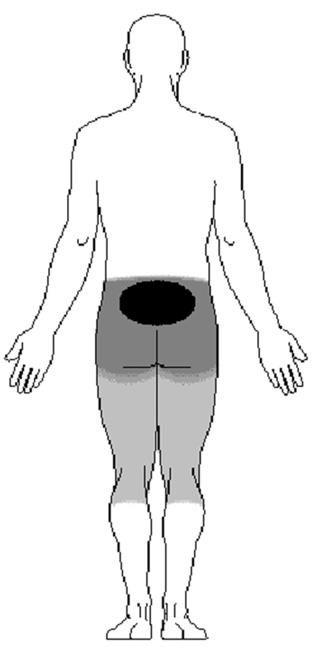

Pain from spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis starts in the center of the lower back and radiates downward.

In many cases, patients with spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis do not have any obvious symptoms. The conditions may not even be discovered until an x-ray is taken for an unrelated injury or condition.

When symptoms do occur, the most common symptom is lower back pain. This pain may:

- Feel similar to a muscle strain

- Radiate to the buttocks and back of the thighs

- Worsen with activity and improve with rest

In patients with spondylolisthesis, muscle spasms may lead to additional signs and symptoms, including:

- Back stiffness

- Tight hamstrings (the muscles in the back of the thigh)

- Difficulty standing and walking

Spondylolisthesis patients who have severe or high-grade slips may have tingling, numbness, or weakness in one or both legs. These symptoms result from pressure on the spinal nerve root as it exits the spinal canal near the fracture.

Doctor Examination

Physical Examination

Your doctor will begin by taking a medical history and asking about your child’s general health and symptoms. He or she will want to know if your child participates in sports. Children who participate in sports that place excessive stress on the lower back are more likely to have a diagnosis of spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis.

Your doctor will carefully examine your child’s back and spine, looking for:

- Areas of tenderness

- Limited range of motion

- Muscle spasms

- Muscle weakness

Your doctor will also observe your child’s posture and gait (the way he or she walks). In some cases, tight hamstrings may cause a patient to stand awkwardly or walk with a stiff-legged gait.

Imaging tests will help confirm the diagnosis of spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis.

Imaging Tests

X-rays. These studies provide images of dense structures, such as bone. Your doctor may order x-rays of your child’s lower back from a number of different angles to look for a stress fracture and to view the alignment of the vertebrae.

If x-rays show a “crack” or stress fracture in the pars interarticularis portion of the fourth or fifth lumbar vertebra, it is an indication of spondylolysis.

Computerized tomography (CT) scans. More detailed than plain x-rays, CT scans can help your doctor learn more about the fracture or slippage and can be helpful in planning treatment.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. These studies provide better images of the body’s soft tissues. An MRI can help your doctor determine if there is damage to the intervertebral disks between the vertebrae or if a slipped vertebra is pressing on spinal nerve roots. It can also help your doctor determine if there is injury to the pars before it can be seen on x-ray.

The goals of treatment for spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are to:

- Reduce pain

- Allow a recent pars fracture to heal

- Return the patient to sports and other daily activities

Nonsurgical Treatment

Initial treatment is almost always nonsurgical in nature. Most patients with spondylolysis and low-grade spondylolisthesis will improve with nonsurgical treatment.

Nonsurgical treatment may include:

Rest. Avoiding sports and other activities that place excessive stress on the lower back for a period of time can often help improve back pain and other symptoms.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and naproxen can help reduce swelling and relieve back pain.

Physical therapy. Specific exercises can help improve flexibility, stretch tight hamstring muscles, and strengthen muscles in the back and abdomen.

Bracing. Some patients may need to wear a back brace for a period of time to limit movement in the spine and provide an opportunity for a recent pars fracture to heal.

Over the course of treatment, your doctor will take periodic x-rays to determine whether the vertebra is changing position.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery may be recommended for spondylolisthesis patients who have:

- Severe or high-grade slippage

- Slippage that is progressively worsening

- Back pain that has not improved after a period of nonsurgical treatment

Spinal fusion between the fifth lumbar vertebra and the sacrum is the surgical procedure most often used to treat patients with spondylolisthesis.

The goals of spinal fusion are to:

- Prevent further progression of the slip

- Stabilize the spine

- Alleviate significant back pain

Surgical Procedure

Spinal fusion is essentially a “welding” process. The basic idea is to fuse together the affected vertebrae so that they heal into a single, solid bone. Fusion eliminates motion between the damaged vertebrae and takes away some spinal flexibility. The theory is that, if the painful spine segment does not move, it should not hurt.

During the procedure, the doctor will first realign the vertebrae in the lumbar spine. Small pieces of bone—called bone graft—are then placed into the spaces between the vertebrae to be fused. Over time, the bones grow together—similar to how a broken bone heals.

Prior to placing the bone graft, your doctor may use metal screws and rods to further stabilize the spine and improve the chances of successful fusion.

In some cases, patients with high-grade slippage will also have compression of the spinal nerve roots. If this is the case, your doctor may first perform a procedure to open up the spinal canal and relieve pressure on the nerves before performing the spinal fusion.

The majority of patients with spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are free from pain and other symptoms after treatment. In most cases, sports and other activities can be resumed gradually with few complications or recurrences.

To help prevent future injury, your doctor may recommend that your child do specific exercises to stretch and strengthen the back and abdominal muscles. In addition, regular check-ups are needed to ensure that problems do not develop.

Spinal Injury- Fractures Of Vertebrae

Osteoporosis and Spinal Fractures

As we get older, our bones thin and our bone strength decreases. Osteoporosis is a disease in which bones become very weak and more likely to break. It often develops unnoticed over many years, with no symptoms or discomfort until a bone breaks.

Fractures caused by osteoporosis most often occur in the spine. These spinal fractures — called vertebral compression fractures — occur in nearly 700,000 patients each year. They are almost twice as common as other fractures typically linked to osteoporosis, such as broken hips and wrists.

Not all vertebral compression fractures are due to osteoporosis. But when the disease is involved, a fracture is often a patient’s first sign of a weakened skeleton from osteoporosis. To learn more about osteoporosis

Your spine is made up of 24 bones, called vertebrae, that are stacked on top of one another. These bones connect to create a canal that protects the spinal cord. Other parts of your spine include:

Spinal cord and nerves. These “electrical cables” travel through the spinal canal carrying messages between your brain and muscles. Nerve roots branch out from the spinal cord through openings in the vertebrae.

Intervertebral disks. In between your vertebrae are flexible intervertebral disks. These flat, round disks are about a half-inch thick. They cushion the vertebrae, acting as shock absorbers when you walk or run.

Normal spine anatomy.

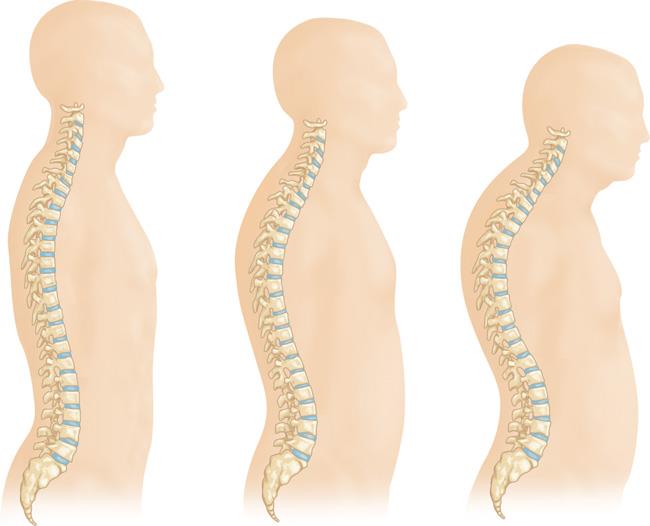

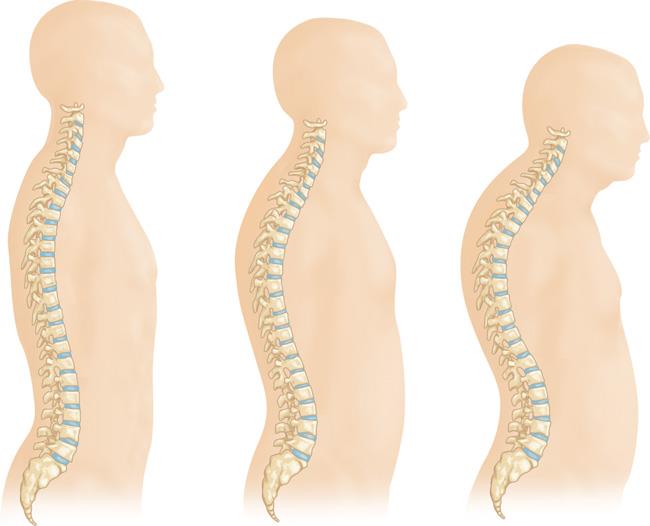

Osteoporosis is a natural aging phenomenon; as we get older, our bones weaken. When the vertebrae in the spine weaken, they can narrow and become flatter. This can make elderly patients shorter and lead to a rounded back, a hump or a “bent forward look” to the spine.

As osteoporosis progresses, the vertebrae weaken and become flatter. This can cause a severely rounded back (“dowager’s hump”).

The weakened vertebrae are at a high risk for fracture. A vertebral compression fracture occurs when too much pressure is placed on a weakened vertebra and the front of it cracks and loses height. Vertebral compression fractures are often the result of a fall, but people with osteoporosis can suffer a fracture even when doing everyday things, such as reaching, twisting, coughing, and sneezing.

A vertebral compression fracture (arrow) has a wedged-shaped appearance. The front of the vertebra has cracked and shortened while the back remains intact.

A vertebral compression fracture causes back pain. The pain typically occurs near the break itself. Vertebral compression fractures most commonly occur near the waistline, as well as slightly above it (mid-chest) or below it (lower back).

The pain often gets worse with motion, particularly when you are changing positions. It is often relieved by rest or lying down. Coughing and sneezing can also make the pain increase. Although the pain may move to other areas of the body (for example, into the abdomen or down the legs), this is uncommon.

Physical Examination

Your doctor will talk with you about your general health and medical history and ask you to describe your symptoms. He or she will then perform a physical exam.

While you are standing, your doctor will examine the alignment, or straightness, of your spine and your posture. He or she will also push on certain places on your back to try and identify whether your pain is from an injury to the muscle or bones.

To make sure there is no injury to the spinal nerve roots, your doctor will conduct a neurologic examination—looking for loss of sensation, changes in reflexes, or muscle weakness.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Fortunately, most people who suffer a vertebral compression fracture get better within 3 months without specific treatment to repair the fracture. Simple measures, such as a short period of rest and limited use of pain medications, are often all that is required. In some cases, patients are instructed to wear a brace to restrict movement and allow the vertebral compression fracture to heal.

If your doctor has also diagnosed osteoporosis, you are at increased risk for additional vertebral compression fractures and other fractures, such as to the hip and wrist. Your doctor will address treatments for bone density loss during this time.

Surgical Treatment

If you have severe pain that does not respond to nonsurgical treatment, then surgery may be considered.

In the past, the only surgical options available to patients with vertebral compression fractures involved extensive procedures. Today, vertebral augmentation procedures offer a minimally invasive alternative.

The two types of vertebral augmentation methods available are kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty. The best candidates for these procedures are patients who suffer severe pain from recent vertebral compression fractures. If you are a candidate for kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty, your doctor will talk with you about which procedure may be better for you based on the type of vertebral compression fracture you have.

Kyphoplasty. In a kyphoplasty, a needle is inserted into the fractured vertebra using an x-ray for guidance. A small device called a balloon tamp is then inserted through the needle and into the fractured vertebra. The balloon tamp is inflated from within the vertebra, which restores the height and shape of the vertebral body. When the balloon tamp is removed, it leaves a cavity that is filled with a special bone cement that strengthens the vertebra.

Several reports have been published on the results of vertebral augmentation procedures. In two large studies, the benefit of vertebroplasty was found to be very short term. In contrast, studies indicate that kyphoplasty may increase function and decrease pain more quickly than nonoperative treatment.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons has reviewed the current research on osteoporotic spinal compression fractures and developed a Clinical Practice Guideline that provides evidence-based information about vertebral augmentation procedures. For more information: .

Your doctor will discuss realistic expectations for recovery if vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty is recommended for you.

Kyphosis (Roundback) Of The Spine

Kyphosis is a spinal disorder in which an excessive outward curve of the spine results in an abnormal rounding of the upper back. The condition is sometimes known as “roundback” or—in the case of a severe curve—as “hunchback.” Kyphosis can occur at any age, but is common during adolescence.

In the majority of cases, kyphosis causes few problems and does not require treatment. Occasionally, a patient may need to wear a back brace or do exercises in order to improve his or her posture and strengthen the spine. In severe cases, however, kyphosis can be painful, cause significant spinal deformity, and lead to breathing problems. Patients with severe kyphosis may need surgery to help reduce the excessive spinal curve and improve their symptoms.

Your spine is made up of three segments. When viewed from the side, these segments form three natural curves.

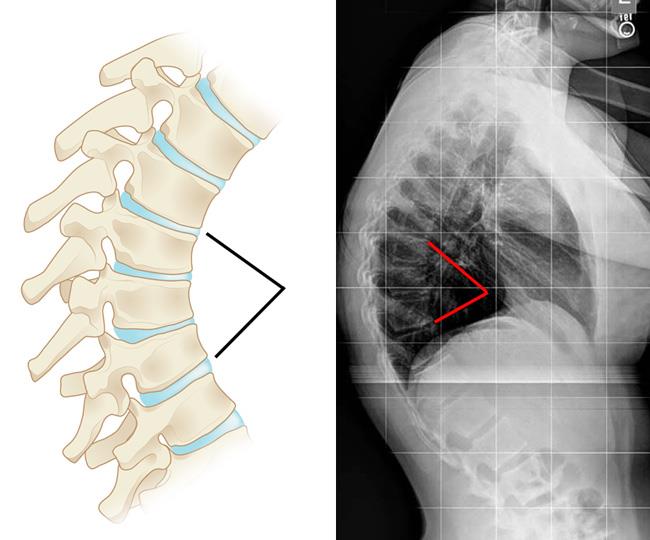

The “c-shaped” curves of the neck (cervical spine) and lower back (lumbar spine) are called lordosis. The “reverse c-shaped” curve of the chest (thoracic spine) is called kyphosis.

This natural curvature of the spine is important for balance and helps us to stand upright. If any one of the curves becomes too large or too small, it becomes difficult to stand up straight and our posture appears abnormal.

When viewed from the side, a normal spine has three gentle curves.

Other parts of your spine include:

Vertebrae. The spine is made up of 24 small rectangular-shaped bones, called vertebrae, which are stacked on top of one another. These bones create the natural curves of your back and connect to create a canal that protects the spinal cord.

Vertebrae and intervertebral disks in a healthy spine.

Intervertebral disks. In between the vertebrae are flexible intervertebral disks. These disks are flat and round and about a half inch thick. Intervertebral disks cushion the vertebrae and act as shock absorbers when you walk or run.

Although the thoracic spine should have a natural kyphosis between 20 to 45 degrees, postural or structural abnormalities can result in a curve that is outside this normal range. While the medical term for a curve that is greater than normal (more than 50 degrees) is actually “hyperkyphosis,” the term “kyphosis” is commonly used by doctors to refer to the clinical condition of excessive curvature in the thoracic spine that leads to a rounded upper back.

Kyphosis can affect patients of all ages. The condition, however, is common during adolescence—a time of rapid bone growth.

Kyphosis can vary in severity. In general, the greater the curve, the more serious the condition. Milder curves may cause mild back pain or no symptoms at all. More severe curves can cause significant spinal deformity and result in a visible hump on the patient’s back.

There are several types of kyphosis. The three that most commonly affect children and adolescents are:

- Postural kyphosis

- Scheuermann’s kyphosis

- Congenital kyphosis

Postural Kyphosis

Postural kyphosis, the most common type of kyphosis, usually becomes noticeable during adolescence. It is noticed clinically as poor posture or slouching, but is not associated with severe structural abnormalities of the spine.

The curve caused by postural kyphosis is typically round and smooth and can often be corrected by the patient when he or she is asked to “stand up straight.”

Postural kyphosis is more common in girls than boys. It is rarely painful and, because the curve does not progress, it does not usually lead to problems in adult life.

Scheuermann’s Kyphosis

Scheuermann’s kyphosis is named after the Danish radiologist who first described the condition.

Like postural kyphosis, Scheuermann’s kyphosis often becomes apparent during the teen years. However, Scheuermann’s kyphosis can result in a significantly more severe deformity than postural kyphosis—particularly in thin patients.

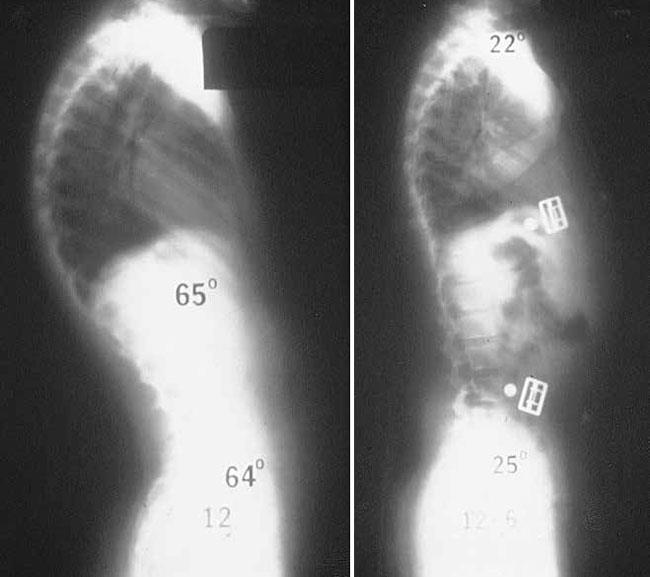

Scheuermann’s kyphosis is caused by a structural abnormality in the spine. In a patient with Scheuermann’s kyphosis, an x-ray from the side will show that, rather than the normal rectangular shape, several consecutive vertebrae have a more triangular shape. This irregular shape causes the vertebrae to wedge together toward the front of the spine, decreasing the normal disk space and creating an exaggerated forward curvature in the upper back.

The curve caused by Scheuermann’s kyphosis is usually sharp and angular. It is also stiff and rigid; unlike a patient with postural kyphosis, a patient with Scheuermann’s kyphosis is not able to correct the curve by standing up straight.

Scheuermann’s kyphosis usually affects the thoracic spine, but occasionally develops in the lumbar (lower) spine. The condition is more common in boys than girls and stops progressing once growing is complete.

Scheuermann’s kyphosis can sometimes be painful. If pain is present, it is commonly felt at the highest part or “apex” of the curve. Pain may also be felt in the lower back. This results when the spine tries to compensate for the rounded upper back by increasing the natural inward curve of the lower back. Activity can make the pain worse, as can long periods of standing or sitting.

Congenital Kyphosis

Congenital kyphosis is present at birth. It occurs when the spinal column fails to develop normally while the baby is in utero. The bones may not form as they should or several vertebrae may be fused together. Congenital kyphosis typically worsens as the child ages.

Patients with congenital kyphosis often need surgical treatment at a very young age to stop progression of the curve. Many times, these patients will have additional birth defects that impact other parts of the body such as the heart and kidneys.

The signs and symptoms of kyphosis vary, depending upon the cause and severity of the curve. These may include:

- Rounded shoulders

- A visible hump on the back

- Mild back pain

- Fatigue

- Spine stiffness

- Tight hamstrings (the muscles in the back of the thigh)

Rarely, over time, progressive curves may lead to:

- Weakness, numbness, or tingling in the legs

- Loss of sensation

- Shortness of breath or other breathing difficulties

Mild kyphosis often goes unnoticed until a scoliosis screening at school—and this prompts a visit to the doctor. If changes to the patient’s back are noticeable, however, it is usually quite troubling for both the parents and the child. Concern about the cosmetic appearance of the child’s back is often what leads the family to seek medical help.

Physical Examination

Your doctor will begin by taking a medical history and asking about your child’s general health and symptoms. He or she will then examine your child’s back, pressing on the spine to determine if there are any areas of tenderness.

In more severe cases of kyphosis, the rounding of the upper back or a hump may be clearly visible. In milder cases, however, the condition may be harder to diagnose.

During the exam, your doctor will ask your child to bend forward with both feet together, knees straight, and arms hanging free. This test, which is called the “Adam’s forward bend test,” enables your doctor to better see the slope of the spine and observe any spinal deformity.

Your doctor may also ask your child to lay down to see if this straightens the curve—a sign that the curve is flexible and may be representative of postural kyphosis.

Tests

X-rays. These studies provide images of dense structures, such as bone. Your doctor may order x-rays from different angles to determine if there are changes in the vertebrae or any other bony abnormalities.

X-rays will also help measure the degree of the kyphotic curve. A curve that is greater than 50 degrees is considered abnormal.

Pulmonary function tests. If the curve is severe, your doctor may order pulmonary function tests. These tests will help determine if your child’s breathing is restricted because of diminished chest space.

Other tests. In patients with congenital kyphosis, progressive curves may lead to symptoms of spinal cord compression, including pain, tingling, numbness, or weakness in the lower body. If your child is experiencing any of these symptoms, your doctor may order neurologic tests or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

The goal of treatment is to stop progression of the curve and prevent deformity. Your doctor will consider several things when determining treatment for kyphosis, including:

- Your child’s age and overall health

- The number of remaining growing years

- The type of kyphosis

- The severity of the curve

Nonsurgical Treatment

Nonsurgical treatment is recommended for patients with postural kyphosis. It is also recommended for patients with Scheuermann’s kyphosis who have curves of less than 75 degrees.

Nonsurgical treatment may include:

Observation. Your doctor may recommend simply monitoring the curve to make sure it does not get worse. Your child may be asked to return for periodic visits and x-rays until he or she is fully grown.

Unless the curve gets worse or becomes painful, no other treatment may be needed.

Physical therapy. Specific exercises can help relieve back pain and improve posture by strengthening muscles in the abdomen and back. Certain exercises can also help stretch tight hamstrings and strengthen areas of the body that may be impacted by misalignment of the spine.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs, including aspirin, ibuprofen and naproxen, can help relieve back pain.

Bracing. Bracing may be recommended for patients with Scheuermann’s kyphosis who are still growing. The specific type of brace and the number of hours per day it should be worn will depend upon the severity of the curve. Your doctor will adjust the brace regularly as the curve improves. Typically, the brace is worn until the child reaches skeletal maturity and growing is complete.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is often recommended for patients with congenital kyphosis.

Surgery may also be recommended for:

- Patients with Scheuermann’s kyphosis who have curves greater than 75 degrees

- Patients with severe back pain that does not improve with nonsurgical treatment

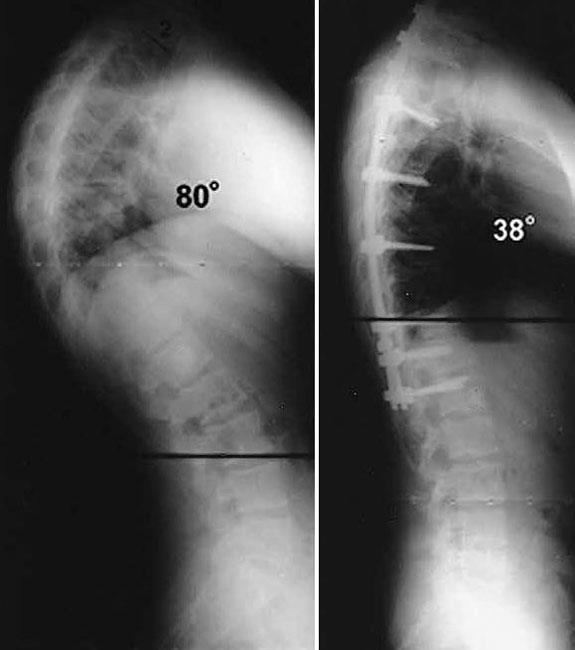

Spinal fusion is the surgical procedure most commonly used to treat kyphosis.

The goals of spinal fusion are to:

- Reduce the degree of the curve

- Prevent any further progression

- Maintain the improvement over time

- Alleviate significant back pain, if it is present

Surgical Procedure

Spinal fusion is essentially a “welding” process. The basic idea is to fuse together the affected vertebrae so that they heal into a single, solid bone. Fusing the vertebrae will reduce the degree of the curve and, because it eliminates motion between the affected vertebrae, may also help alleviate back pain.

During the procedure, the vertebrae that make up the curve are first realigned to reduce the rounding of the spine. Small pieces of bone—called bone graft—are then placed into the spaces between the vertebrae to be fused. Over time, the bones grow together—similar to how a broken bone heals.

Before the bone graft is placed, your doctor will typically use metal screws, plates and rods to increase the rate of fusion and further stabilize the spine.

Exactly how much of the spine is fused depends upon the size of your child’s curve. Only the curved vertebrae are fused together. The other bones in the spine can still move and assist with bending, straightening, and rotation.

If kyphosis is diagnosed early, the majority of patients can be treated successfully without surgery and go on to lead active, healthy lives. If left untreated, however, curve progression could potentially lead to problems during adulthood. For patients with kyphosis, regular check-ups are necessary to monitor the condition and check progression of the curve.

Spinal Injury- Fractures Of Vertebrae

Osteoporosis and Spinal Fractures

As we get older, our bones thin and our bone strength decreases. Osteoporosis is a disease in which bones become very weak and more likely to break. It often develops unnoticed over many years, with no symptoms or discomfort until a bone breaks.

Fractures caused by osteoporosis most often occur in the spine. These spinal fractures — called vertebral compression fractures — occur in nearly 700,000 patients each year. They are almost twice as common as other fractures typically linked to osteoporosis, such as broken hips and wrists.

Not all vertebral compression fractures are due to osteoporosis. But when the disease is involved, a fracture is often a patient’s first sign of a weakened skeleton from osteoporosis. To learn more about osteoporosis

Your spine is made up of 24 bones, called vertebrae, that are stacked on top of one another. These bones connect to create a canal that protects the spinal cord. Other parts of your spine include:

Spinal cord and nerves. These “electrical cables” travel through the spinal canal carrying messages between your brain and muscles. Nerve roots branch out from the spinal cord through openings in the vertebrae.

Intervertebral disks. In between your vertebrae are flexible intervertebral disks. These flat, round disks are about a half-inch thick. They cushion the vertebrae, acting as shock absorbers when you walk or run.

Normal spine anatomy.

Osteoporosis is a natural aging phenomenon; as we get older, our bones weaken. When the vertebrae in the spine weaken, they can narrow and become flatter. This can make elderly patients shorter and lead to a rounded back, a hump or a “bent forward look” to the spine.

As osteoporosis progresses, the vertebrae weaken and become flatter. This can cause a severely rounded back (“dowager’s hump”).

The weakened vertebrae are at a high risk for fracture. A vertebral compression fracture occurs when too much pressure is placed on a weakened vertebra and the front of it cracks and loses height. Vertebral compression fractures are often the result of a fall, but people with osteoporosis can suffer a fracture even when doing everyday things, such as reaching, twisting, coughing, and sneezing.

A vertebral compression fracture (arrow) has a wedged-shaped appearance. The front of the vertebra has cracked and shortened while the back remains intact.

A vertebral compression fracture causes back pain. The pain typically occurs near the break itself. Vertebral compression fractures most commonly occur near the waistline, as well as slightly above it (mid-chest) or below it (lower back).

The pain often gets worse with motion, particularly when you are changing positions. It is often relieved by rest or lying down. Coughing and sneezing can also make the pain increase. Although the pain may move to other areas of the body (for example, into the abdomen or down the legs), this is uncommon.

Physical Examination

Your doctor will talk with you about your general health and medical history and ask you to describe your symptoms. He or she will then perform a physical exam.

While you are standing, your doctor will examine the alignment, or straightness, of your spine and your posture. He or she will also push on certain places on your back to try and identify whether your pain is from an injury to the muscle or bones.

To make sure there is no injury to the spinal nerve roots, your doctor will conduct a neurologic examination—looking for loss of sensation, changes in reflexes, or muscle weakness.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Fortunately, most people who suffer a vertebral compression fracture get better within 3 months without specific treatment to repair the fracture. Simple measures, such as a short period of rest and limited use of pain medications, are often all that is required. In some cases, patients are instructed to wear a brace to restrict movement and allow the vertebral compression fracture to heal.

If your doctor has also diagnosed osteoporosis, you are at increased risk for additional vertebral compression fractures and other fractures, such as to the hip and wrist. Your doctor will address treatments for bone density loss during this time.

Surgical Treatment

If you have severe pain that does not respond to nonsurgical treatment, then surgery may be considered.

In the past, the only surgical options available to patients with vertebral compression fractures involved extensive procedures. Today, vertebral augmentation procedures offer a minimally invasive alternative.

The two types of vertebral augmentation methods available are kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty. The best candidates for these procedures are patients who suffer severe pain from recent vertebral compression fractures. If you are a candidate for kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty, your doctor will talk with you about which procedure may be better for you based on the type of vertebral compression fracture you have.

Kyphoplasty. In a kyphoplasty, a needle is inserted into the fractured vertebra using an x-ray for guidance. A small device called a balloon tamp is then inserted through the needle and into the fractured vertebra. The balloon tamp is inflated from within the vertebra, which restores the height and shape of the vertebral body. When the balloon tamp is removed, it leaves a cavity that is filled with a special bone cement that strengthens the vertebra.

Several reports have been published on the results of vertebral augmentation procedures. In two large studies, the benefit of vertebroplasty was found to be very short term. In contrast, studies indicate that kyphoplasty may increase function and decrease pain more quickly than nonoperative treatment.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons has reviewed the current research on osteoporotic spinal compression fractures and developed a Clinical Practice Guideline that provides evidence-based information about vertebral augmentation procedures. For more information: .

Your doctor will discuss realistic expectations for recovery if vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty is recommended for you.

Infections Of Spine - Tuberculosis

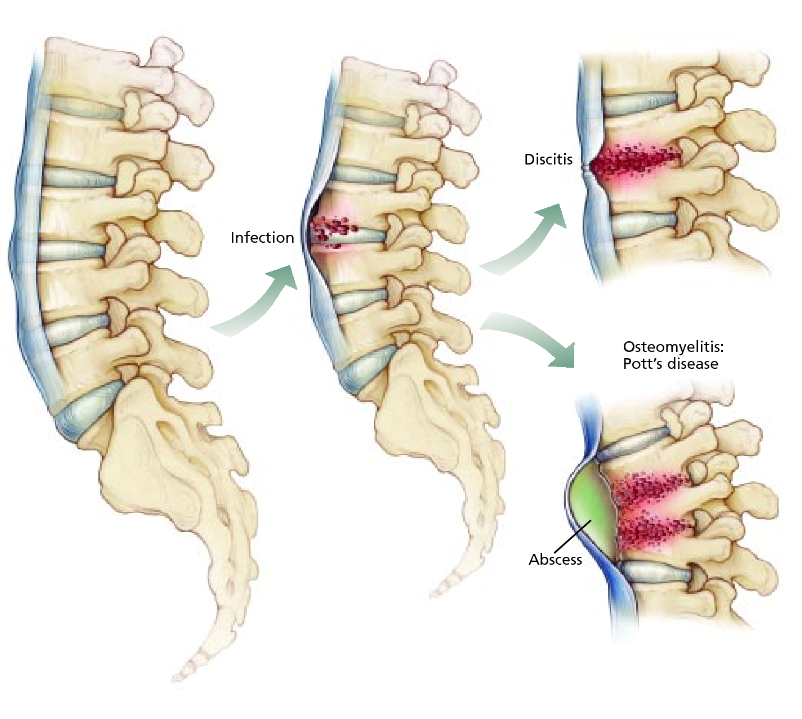

Spinal infections can be classified by the anatomical location involved: the vertebral column, intervertebral disc space, the spinal canal and adjacent soft tissues. Infection may be caused by bacteria or fungal organisms and can occur after surgery. Most postoperative infections occur between three days and three months after surgery.

Vertebral osteomyelitis is the most common form of vertebral infection. It can develop from direct open spinal trauma, infections in surrounding areas and from bacteria that spreads to a vertebra from the blood.

Intervertebral disc space infections involve the space between adjacent vertebrae. Disc space infections can be divided into three subcategories: adult hematogenous (spontaneous), childhood (discitis) and postoperative.

Spinal canal infections include spinal epidural abscess, which is an infection that develops in the space around the dura (the tissue that surrounds the spinal cord and nerve root). Subdural abscess is far rarer and affects the potential space between the dura and arachnoid (the thin membrane of the spinal cord, between the dura mater and pia mater). Infections within the spinal cord parenchyma (primary tissue) are called intramedullary abscesses.

Adjacent soft-tissue infections include cervical and thoracic paraspinal lesions and lumbar psoas muscle abscesses. Soft-tissue infections generally affect younger patients and are not seen often in older people.

- Vertebral osteomyelitis affects an estimated 26,170 to 65,400 people annually.

- Epidural abscess is relatively rare, with 0.2 to 2 cases per every 10,000 hospital admissions. However, 5-18% of patients with vertebral osteomyelitis or disc space infection caused by contiguous spread will develop an epidural abscess.

- Some studies suggest that the incidence of spinal infections is now increasing. This spike may be related to increased use of vascular devices and other forms of instrumentation and to a rise in intravenous drug abuse.

- About 30-70% of patients with vertebral osteomyelitis have no obvious prior infection.

- Epidural abscess can occur at any age, but is most prevalent in people age 50 and older.

- Although treatment has improved greatly in recent years, the death rate from spinal infection is still an estimated 20%.

Risk factors for developing spinal infection include conditions that compromise the immune system, such as:

- Advanced age

- Intravenous drug use

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

- Long-term systemic usage of steroids

- Diabetes mellitus

- Organ transplantation

- Malnutrition

- Cancer

Surgical risk factors include surgeries of long duration, high blood loss, implantation of instrumentation and multiple, or revision, surgeries at the same site. Infections occur in 1-4% of surgical cases, despite numerous preventative measures that are followed.

Spinal infections can be caused by either a bacterial or a fungal infection in another part of the body that has been carried into the spine through the bloodstream. The most common source of spinal infections is a bacterium called staphylococcus aureus, followed by Escherichia coli.

Spinal infections may occur after a urological procedure, because the veins in the lower spine come up through the pelvis. The most common area of the spine affected is the lumbar region. Intravenous drug abusers are more prone to infections affecting the cervical region. Recent dental procedures increase the risk of spinal infections, as bacteria that may be introduced into the bloodstream during the procedure can travel to the spine.

Intervertebral disc space infections probably begin in one of the contiguous end plates, and the disc is infected secondarily. In children, there is some controversy as to the origin. Most cultures and biopsies in children are negative, leading experts to believe that childhood discitis may not be an infectious condition, but caused by partial dislocation of the epiphysis (the growth area near the end of a bone), as a result of a flexion injury.

Symptoms vary depending on the type of spinal infection but, generally, pain is localized initially at the site of the infection. In postoperative patients, these additional symptoms may be present:

- Wound drainage

- Redness, swelling or tenderness near the incision

- Severe back pain

- Fever

- Chills

- Weight loss

- Muscle spasms

- Painful or difficult urination

- Neurological deficits: weakness and/or numbness of arms or legs, incontinence of bowels and/or bladder

Adult patients often progress through the following clinical stages:

- Severe back pain with fever and local tenderness in the spinal column

- Nerve root pain radiating from the infected area

- Weakness of voluntary muscles and bowel/bladder dysfunction

- Paralysis

In children, the most overt symptoms are prolonged crying, obvious pain when the area is palpated and hip tenderness.

Adjacent Soft-tissue Infections

In general, symptoms are usually nonspecific. If a paraspinal abscess is present, the patient may experience flank pain, abdominal pain or a limp. If a psoas muscle abscess is present, the patient may feel pain radiating to the hip or thigh area.

When & How to Seek Medical Care

Seek medical care if symptoms of a spinal infection are present. Early diagnosis and treatment can prevent progression of the infection and may limit the degree of intervention required to treat the infection. Delaying care may result in progression of the infection causing irreversible damage to boney and soft tissue structures of and around the spine.

Signs of spinal infection emergency (Seek care immediately):

- Development of new neurological deficits, such as weakness of arms or legs and/or bowel/bladder incontinence.

- Fever not controlled with medication.

The biggest challenge is making an early diagnosis before serious morbidity occurs. Diagnosis typically takes an average of one month, but can take as long as six months, impeding effective and timely treatment. Many patients do not seek medical attention until their symptoms become severe or debilitating.

Laboratory Tests

Specific laboratory tests can be useful in helping to diagnose a spinal infection. It may be beneficial to get blood tests for acute-phase proteins, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. Both ESR and CRP tests are often good indicators as to whether any inflammation is present in the body (the higher the level, the more likely it is that inflammation is present). As inflammation is the body’s natural response to infection, these markers can monitored to assess the presence of infection and the effectiveness of treatment. These tests alone however, are limited, and other diagnostic tools are usually required.

Identification of the organism is essential, and this can be accomplished through computed tomography-guided biopsy sampling of the vertebra or disc space. Blood cultures, preferably taken during a fever spike, can also help identify the pathogen involved in the spinal infection. Proper identification of the of the pathogen is necessary to narrow the antibiotic treatment regiment.

Spinal infections often require long-term intravenous antibiotic or antifungal therapy and can equate to extended hospitalization time for the patient. Immobilization may be recommended when there is significant pain or the potential for spine instability. If the patient is neurologically and the spinal column is structurally stable, antibiotic treatment should be administered after the organism causing the infection is properly identified. Patients generally undergo antimicrobial therapy for a minimum of six to eight weeks. The type of medication is determined on a case-by-case basis depending on the patient’s specific circumstances, including his or her age.

Nonsurgical treatment should be considered first when patients have minimal or no neurological deficits and the morbidity and mortality rate of surgical intervention is high. However, surgery may be indicated when any of the following situations are present:

- Significant bone destruction causing spinal instability

- Neurological deficits

- Sepsis with clinical toxicity caused by an abscess unresponsive to antibiotics

- Failure of needle biopsy to obtain needed cultures

- Failure of intravenous antibiotics alone to eradicate the infection

The primary goals of surgery are to:

- Debride (clean and remove) the infected tissue

- Enable the infected tissue to receive adequate blood flow to help promote healing

- Restore spinal stability with the use of instrumentation to fuse the unstable spine

- Restore function or limit the degree of neurological impairment

Once it is determined that the patient requires surgery, imaging tools such as plain x-rays, CT scans or MRI can help further pinpoint the level at which to perform surgery.